Gisela McDaniel

@giselamcdaniel

Gisela McDaniel is a diasporic, indigenous Chamorro artist, and one of my personal favourites.

If you are able, I strongly encourage you to read McDaniel’s interview. We discuss some important topics, including the continued battle for Native Hawaiians to protect their lives against environmental threats to their indigenous Ohana and sacred sites.

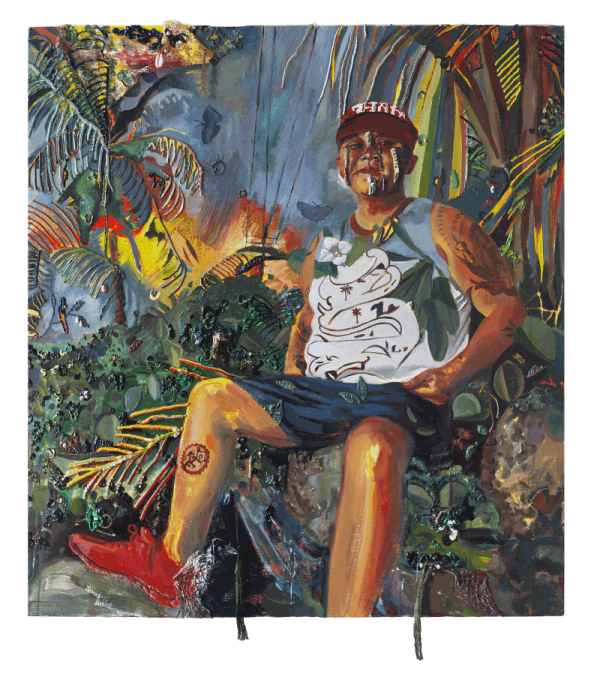

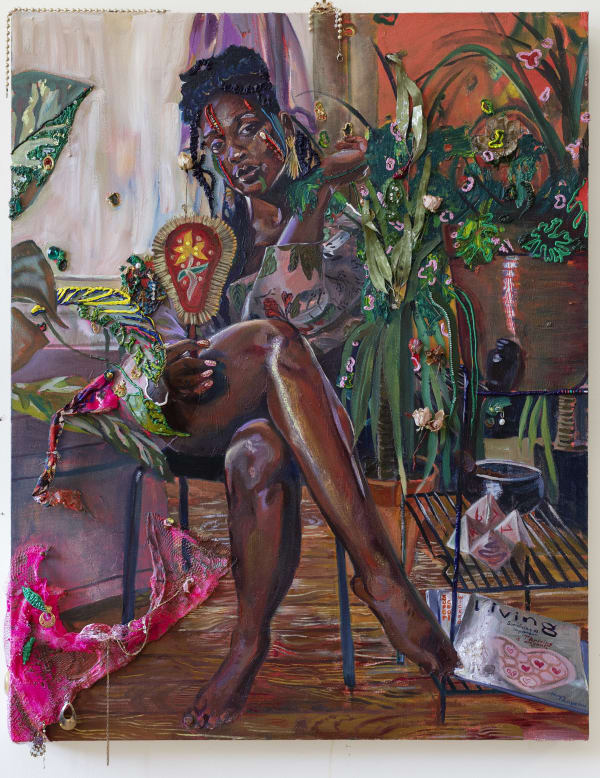

McDaniel’s work is unbelievable. The tactility, intimacy, richness and multi-facited nature of her works are derived in response to her own healing after a trauma, and they reflect the similar healing of women and non-binary people. In three words, she describes her work as: “Vibrant, Indigenous, Feminist”.

When asking McDaniel about what she hopes her work says to the viewer, her answer is, I think, something everyone should read. She said:

“Empathy, perspective, and humility. You never know what your peers, colleagues, strangers, or friends are really going through until you ask. There is so much people hold inside or feel they can’t speak about freely, especially now as some folx are questioning the power of story-telling and focusing on being a survivor. The truth is that their experiences and the stories they have to tell about living their lives is an act of resistance in and of itself. I just want to give credit where it is greatly overdue. “

-

INTERVIEW

My first question, Gisela, is every artist has a story of how they became an artist. What was your earliest memory surrounding artwork? And was there a moment it clicked that you would be an artist, or has it never been a question?

I began drawing when I was very young. When I was about eight, I drew a not very pretty but fairly realistic self-portrait. After that my mother enrolled me in drawing classes at a local community-based art center. Art has been a part of who I am ever since.

You are so multidisciplinary with your work, in oil painting, audio and censored technology. Tell us a bit about how these interact?

The audio is embedded with sensors on the surface of the painting. When someone enters the “personal space” of the piece, it literally triggers the audio, an obvious play on the term “to be triggered”. The subject of the painting literally interacts with and speaks to the viewer through the audio recording, thereby exercising control over their image and story, wherever the piece is located. It was crucial to me that people HAD to listen to the voices of the subjects in order to view the piece.

Sometimes the audio works differently and has different meanings depending on the topic of the audio piece. For example, most of my motion-censored work involved stories of sexualized violence. In this instance, the audio and the way the painting is exhibited demands that the viewer be respectful of the subject’s and the painting's boundaries, so to speak. In other words, I am intentionally prioritizing the subject’s ability to exert a form of power wherever her story and the painting travels.

How has your work changed throughout your painting career? Have you always been a figurative painter?

Yes. Painting a human form, for me, involves an actual commitment to that person and depth of feeling. To render flesh is an incredibly intimate act and a way of honoring someone’s identity and humanity. Everything else is secondary. I’ve also always been drawn to depict nature, sometimes from life, sometimes as something that I’m creating as part of a composition. As a member of the diaspora and an indigenous Chamorro woman (from Guahan)- but not physically being on the Island - I’ve always found myself fantasizing about that landscape growing up Midwest and now living in Detroit.

Who are the figures and portraits in your work? What are your encounters with these figures?

All the figures, or subjects, are women and non-male people that I encounter personally or connect to by word of mouth. We sit down and share stories with one another that are often incredibly heavy to carry. Doing so allows us to create and hold space to safely unburden themselves/ourselves of these experiences and to examine how they shape how we live and move in the world. Subjects are allowed to share as little or as much as they’d like and always have control over how they choose to pose. They decide how much or how little they choose to “censor” or reveal in terms of their own bodies, whether fully clothed or nude. I deliberately avoid focusing on moments of violence, but rather on celebrating how subjects now move through and beyond those experiences: often with incredible grace and resilience.

How do you go from these encounters to your final artworks?

I edit the audio into pieces that accompany the paintings so that the subject’s voice will always exist alongside their portraits. I find myself heavily reflecting on the stories shared and allow them to guide the painting process and determine the final outcome. The mask is painted last, as a final boundary between the subject and the eventual gaze of a viewer. When I first started this work, I was working in Detroit where many of the subjects also lived. It was important to maintain the subjects’ anonymity and protect their safety. Over time, I found that some of the subjects wanted to be known, so the masks also evolved to reflect their wishes.

Talk to us about your vivid colour palette and what it means for you and your work?

As an indigenous Pacific Islander woman, I am deeply influenced and also disturbed by the work of Paul Guaguin. I remember having a professor in an undergrad painting class tell me I was using a similar palette to his. My mother, a feminist sociologist loathed Gauguin, which is why, I didn’t immediately recognize his name. She’d never mentioned him in our home and pretty much flipped out when I shared my professor’s comment. She wasn’t angry at the professor, but talked about the anger she felt watching white art patrons viewing Gaugin at the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) while she struggled to be seen as a Pacific Islander woman and graduate student. To me, these colors belong more to my people then they would ever to him - particularly, as a white, male, Western artist and so-called “Father of Primitivism”. So I was seeking, maybe subconsciously at the beginning, and now consciously, to reclaim these colors.

-

-

Who or what are your biggest inspirations? How do you find them and how do they come out in your work?

My biggest inspiration is my subjects. The grace with which they move through life inspires and amazes me. I’m deeply honored to have their trust. I feel very driven to do the best possible job for them by creating a beautiful portrait and accompanying audio. I really want them to feel and to see themselves represented as the powerful and beautiful people they are. The paintings are also a way to document their story, who they are and to record their journeys of healing for posterity.

Tell me about your studio? What are your artist essentials, and what does an average working day look like for you?

I spend every day in the studio unless I am interviewing. I keep lots of plants around me for inspiration, as well as flowers I dry for the paintings. I usually listen to podcasts or books while I work and the day flies by.

What do you hope your work brings to the viewers?

Empathy, perspective, and humility. You never know what your peers, colleagues, strangers, or friends are really going through until you ask. There is so much people hold inside or feel they can’t speak about freely, especially now as some folx are questioning the power of story-telling and focusing on being a survivor. The truth is that their experiences and the stories they have to tell about living their lives is an act of resistance in and of itself. I just want to give credit where it is greatly overdue.

What are you working on at the moment?

A community-based organization recently commissioned me to paint a mural of Gina DeJesus in Cleveland, Ohio. Gina was one of three young women whose stories made national headlines. They were kidnapped and held against their will for several years by a vicious coward who eventually took his own life in jail. I remember hearing her story growing up, as she didn’t live far from me. I am deeply honored to publicly memorialize her strength and resilience. The mural is being painted on the building where the Gina DeJesus Foundation for Missing, Abducted and Exploited Children and Adults will be located. I’m also working on several paintings that will be exhibited at the upcoming online Frieze Gallery exhibition. Finally, in September, Pilar Corrias Gallery (based in London) which recently began representing me last spring, is debuting a solo exhibition of my work called, “Making WAY/FARING Well”. Please be sure to check it out!

What would your dream project be?

I would love to paint Rihanna. She was the first representation of a really powerful “Island Girl” I’d ever seen in popular culture/the music scene that I related to. She also went through a very public experience with domestic violence but never let that stop her from being the amazing force she is in the world. Her music has gotten me through some dark times. The way she continues to grow, to create and to THRIVE has always inspired me.

What 3 words would you use to describe your artwork?

Vibrant, Indigenous, Feminist

-

Favourite historical female artist(s)?

Nikki de Saint Phalle and Frida Khalo

Favourite current practicing female artist?

Jordan Casteel

Who should She Curates interview next?

Would love to see you interview my friend Bree, a Black Detroit-based artist. https://www.gant.studio

Is there anything else you wanted to say?

Please be sure to spread the word about continued efforts to resist U.S. militarization and environmental threats posted to Guahan (Guam) by following the Facebook page of: “Prutehi Litekyan” (Protect Ritidian) at: https://www.facebook.com/saveritidian/ and reading a recent update on the situation in this article: “Ancient Burial Ground Unearthed on Guam” at https://www.rnz.co.nz/international/pacific-news/423000/ancient-burial-ground-unearthed-on-guam?fbclid=IwAR3Ij0XbmfPe_szNR90t_4daHcYWe0VsJTMLdcrr7rLeENPKpl3yq78GjRg

Native Hawaiians also continue to fight to protect their way of life and environmental threats to to their indigenous Ohana and sacred sights. Readers can follow and support developments by following Protect Mauna Kea at: https://www.facebook.com/protectmaunakea/

Dangkalu Si Yu’os Ma’ase (Thank you very much).